Debating China's economic future

Panelists:

- Michael Pettis, professor of finance, Peking University

- Victor Gao, director of the China National Association of International Studies; former translator for Deng Xiaoping

Pettis said he believes China faces an inevitable and painful transition, with economic growth falling to a 3-4% rate in the next decade. Its growth model involves a systematic transfer of wealth from the household sector to support growth, and three mechanisms facilitate this process:

- Undervalued currency: a direct subsidy on the net export sector, but a consumption tax on households.

- Widening gap between Chinese wage growth and productivity growth: reduces labor's share of GDP.

- Financial repression: low interest rates transfer wealth from savers to borrowers.

Pettis said he believes that as marginal returns on capital slow, it will become more difficult to find economically viable projects. China's savings rate will need to decline and its consumption-to-GDP ratio must increase, which will only occur if household income captures a larger share of GDP. Pettis outlined four policy options:

- Reverse transfer mechanism from households to other sectors, leading to a sharp increase in the value of the yuan and potential major recession (unrealistic).

- Gradually reduce distortions, which could take a decade (they've run out of time).

- Massive privatization program to transfer wealth from state sector to households (politically difficult).

- Expand government debt to absorb private-sector debt (possible, but economically inefficient).

Gao countered with a far-more-upbeat assessment, though he liberally relied on history and China's great transformation over the past three decades. He said he expects China's economy to continue to grow at close to 8% thanks to four megatrends he doesn't believe will change: industrialization, modernization, urbanization and globalization.

Our view

At Schwab, we believe that as China's economy matures and shifts from over-reliance on government investment to increased private consumption as a percent of GDP, slower growth is likely the new normal. However, this transition won't be accomplished overnight; the government will likely need to enact market-based reforms and reduce its grip on the economy, and the transition could be accompanied by bumps in the road.

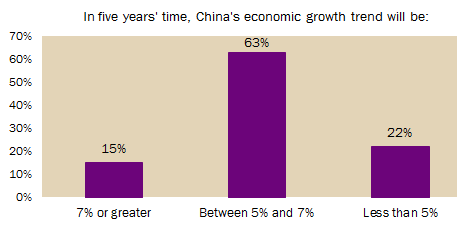

Our view on China's economic trajectory is in keeping with the results of a poll during the conference:

Source: BCA Research Inc., as of September 18, 2012.